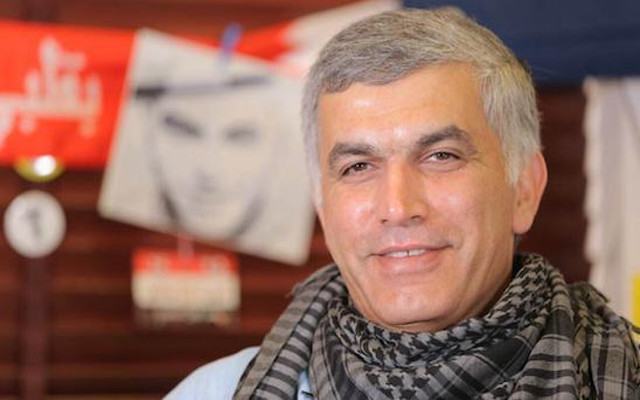

On 13 June 2016, the Government of Bahrain arrested prominent human rights defender Nabeel Rajab from his home. The Government did not initially justify the arrest, but later stated that he had committed crimes against the Bahraini State in making statements over Twitter. Mr. Rajab has been incarcerated initially in East Riffa Police Station and subsequently West Riffa Police Station since that time. Throughout the period of his detention, he has been placed in solitary confinement in squalid and unsanitary conditions. The period of his pre-trial detention has been consistently renewed by the Office of the Public Prosecution. His initial trial date is scheduled for Monday, 1 August 2016.

Click here to download this article.

The detention and treatment of Nabeel is violative of international human rights law applicable to Bahrain. The Government of Bahrain has acceded to numerous international human rights treaties that prohibit both government persecution for actions associated with the freedom of expression, assembly, and thought and the abusive treatment of prisoners. This paper, argued in two parts, will outline the manner by which the Government’s treatment of Nabeel is illegal. Part one will dissect and analyze the illegality of Nabeel’s arrest, detention, and prosecution, while part two will consider the government treatment of Nabeel during his detention. The paper concludes that both the arrest of Nabeel and his subsequent treatment are illegal under international law, and closes by suggesting appropriate remedy that the government should provide for its trespasses.

- Arrest and Prosecution

Facts

Nabeel Rajab is a well-known human rights defender working in the Kingdom of Bahrain. The Bahraini government has repeatedly targeted Nabeel in the past in relation to his work in defending human rights. As a result, Nabeel has been the subject of numerous international communications defending his work and calling for his fair treatment, including a decision by the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention that a previous detention was arbitrary in character.

On 13 June 2016, as part of a wider government assault on civil society, free expression, and political dissent, Bahraini authorities re-arrested Nabeel. Security forces from the Ministry of Interior Cybercrimes Unit surrounded Nabeel’s home. They arrested Nabeel and confiscated all of his electronic devices.

On 26 June, authorities told Nabeel that a previous case against him concerning comments that Nabeel made regarding torture at Jau Prison and the war in Yemen had been referred to the High Court. In the comments regarding Jau Prison, Nabeel documented allegations of torture and other forms of abuse emanating from the prison. For these comments, authorities charged Nabeel with “spreading false news and rumors about the internal situation in a bid to discredit Bahrain” under Article 134 of the Penal Code, and “insulting a statutory body” under Article 216 of the Penal Code. In his comments on Yemen, also published over Twitter, Nabeel criticized Bahrain’s involvement in the Saudi-led coalition intervening in the country, especially as regarded the high human cost of the war. For these comments, the government charged him with “spreading false news in a time of war.”[1]

Pertinent International Law

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a legally-binding instrument in international human rights law that provides input upon the rights and freedoms of assembly, expression, and thought. Bahrain acceded to the ICCPR on 20 September 2006 with three reservations, none of which mention or affect any of the above-mentioned rights, except insofar as the freedom of thought affects religion and Islamic Sharia.[2] Having acceded without reservation upon the articles providing the rights of assembly and expression, their text controls throughout the Kingdom of Bahrain without modification or input from the Government. The text of the article concerning freedom of thought also controls throughout the Kingdom insofar as it applies to political thought.

Article 19 of the ICCPR in pertinent part reads:

- Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

- The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.[3]

Accordingly, the ICCPR provides the right to hold an opinion and express that opinion through any medium, so long as that opinion or expression does not harm the reputation or rights of others, harm national security or public order, or harm public health or morals. The ICCPR does not provide further guidance as to the meaning of these exceptions. However, the Committee on Human Rights, the body established by the ICCPR to maintain the treaty and guard its interests, has elaborated on what the national security exception entails.

In General Comment No. 34, the Committee explained that the exceptions in the ICCPR do not apply to the freedom of opinion.

“Paragraph 1 of article 19 requires protection of the right to hold opinions without interference. This is a right to which the Covenant permits no exception or restriction. Freedom of opinion extends to the right to change an opinion whenever and for whatever reason a person so freely chooses. No person may be subject to the impairment of any rights under the Covenant on the basis of his or her actual, perceived or supposed opinions.”[4]

Further in the General Comment, the Committee explained that the exceptions for reputation and national security to the freedom of expression may never be invoked to justify persecution on the basis of freedom of speech advocating for democracy or human rights.

“Paragraph 3 may never be invoked as a justification for the muzzling of any advocacy of multi-party democracy, democratic tenets and human rights. Nor, under any circumstance, can an attack on a person, because of the exercise of his or her freedom of opinion or expression, including such forms of attack as arbitrary arrest, torture, threats to life and killing, be compatible with article 19.”

Beyond the international commitments associated with the ICCPR, international judicial and arbitrative bodies have also ruled upon the application of international law in situations of detention on grounds related to free expression. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, empowered by the Human Rights Council to make official decisions regarding the arbitrary character of detentions, has repeatedly found that a detention is arbitrary when is based solely on the grounds of an act of expression critical of or dissenting against a government. This was the case in opinion No. 12/2013 (Bahrain), itself concerning Nabeel. In 2013, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found that, “… it is clear that Mr. Rajab was detained and convicted under existing domestic laws in Bahrain, which seem to deny persons the basic right to freedom of opinion, expression, and assembly…” and stated that, therefore, Nabeel’s detention at that point had been arbitrary.[5] Numerous further Working Group decisions have held identically upon these grounds.[6]

Discussion

Nabeel’s arrest and prosecution under Articles 133, 134, and 216 of the Bahraini penal code are illegal under international law. Article 19 of the ICCPR guarantees Nabeel the right to freely express his political opinions and views. Insofar as they violate that right to free expression, Articles 133, 134, and 216 are illegitimate, and any prosecution under their purview would violate human rights law.

Article 133

Article 133 of the Bahraini Penal Code violates international human rights law and Bahrain’s commitments under the ICCPR. Article 133 states,

“A punishment of imprisonment for a period not exceeding 10 years shall be inflicted upon any person who deliberately announces in wartime false or malicious news, statements or rumors or mounts adverse publicity campaigns, so as to cause damage to military preparations for defending the State of Bahrain or military operations of the Armed Forces, to cause people to panic or to weaken the nation’s perseverance.”[7]

Bahraini Penal Code Article 133 violates Article 19(2) of the ICCPR. Specifically, in criminalizing, “deliberately announc[ing]… statements… or mount[ing] adverse publicity campaigns… to weaken the nation’s perseverance,” the Government of Bahrain impedes upon the ICCPR Article 19(2) right to “impart information… of all kinds, regardless of frontiers.”

Article 134

In arresting Nabeel and charging him under Article 134 of the Penal Code, the Government of Bahrain violated international law. Article 134 of the Penal Code itself is illegal under international law. Article 134 states,

“A punishment of imprisonment for at least 3 months and a fine of at least BD 100, or either penalty, shall be inflicted upon every citizen who deliberately releases abroad false or malicious news, statements or rumors about domestic conditions in the State, so as to undermine financial confidence in the State or adversely affect its prestige or position, or exercises in any manner whatsoever activities that are harmful to the national interests.”[8]

Article 134 of the Bahraini Penal Code is incompatible with Article 19(2) of the ICCPR. Article 19(2) states clearly that, “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers…” In this case, Bahraini Penal Code Article 134’s provisions stating that persons deliberately releasing “… malicious news, statements or rumors about domestic conditions in the State,” regardless of reason, conflicts with ICCPR Article 19(2)’s freedom to “impart information… of all kinds, regardless of frontiers.”

Aside from its specific prescriptions being illegal under Article 19(2) of the ICCPR, Article 134 is also overly broad, especially as it relates to the exercise “in any manner whatsoever of activities that are harmful to the national interest.” Article 134 allows the government to set national interest and thereafter decide what activity harms that interest; it can cover any activity upon which the government decides. In this manner, not only does Article 134 of the Penal Code excessively abridge the right to free expression, but it also creates a situation in which the government may create law and retroactively apply it. Should the government dislike an activity that is not actively illegal in the Penal Code, Article 134 allows the government to decide that that activity harms national interest, thereby allowing the government to seek prosecution. Insofar as this provision would impinge upon the freedom of expression guarantees provided by ICCPR Article 19(2), it is illegal under international law on account of overreach.

Article 216

In arresting Nabeel and charging him under Article 216, the Government of Bahrain has further violated international law. Article 216 is itself violative of international law. Article 216 states,

“A person shall be liable for imprisonment or payment of a fine if he offends, by any method of expression the National Assembly, or other constitutional institutions, the army, law courts, authorities or government agencies.”[9]

In the same manner as Articles 133 and 134 violate international law, Penal Code Article 216 further violates Bahrain’s legal human rights commitments. Specifically, the Article in question’s language concerning offending any government agency impermissibly encroaches upon the ICCPR’s right to freely impart information regardless of medium.

Reputation National Security Exception

The Bahraini government would contend that the reputation and national security exceptions contained in Article 19(3)(a) and (b) permits Article 134. The reputation exception states that the exercise of freedom of expression can be limited insofar as it would damage the rights and reputation of others. The national security exception states that the exercise of freedom of expression can be limited for the protection of national security. However, the Committee on Human Rights clarified in General Comment No. 34 that these exceptions can never be used to justify persecution on the basis of acts of free expression related to the advocacy of democracy and human rights. In this case, Nabeel’s comments relate to advocacy for democracy and human rights, as he commented on the use of torture in Jau Prison and the human rights impacts of the war on Yemen. Therefore, these exceptions cannot be applied.

Special analysis must be made for Penal Code Article 216, which, when read in light of the General Comment, must be understood as striking at the foundation of the ICCPR. According to the General Comment, “the free communication of information and ideas about public and political issues between citizens, candidates, and elected representatives is essential.” The Committee further elaborated later in the Comment that restrictions related to reputation “must not impede political debate,” and that the restriction applied to individuals and communities only, without regard to political institutions. In criminalizing any speech offending any government agency, the Government of Bahrain has not only violated the letter of the ICCPR, but also its spirit in that the agreement enshrined the protection of political debate and speech. Penal Code Article 216 is thereby illegal under international law.

Similarity to Previous Detention

Nabeel’s specific situation is analogous to that in which he found himself in 2013, when the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention decided in his favor. In Opinion No. 12/2013 (Bahrain), the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found that, because Nabeel’s detention had been based on a conviction relating to his acts of free expression, it was illegal under international law. Specifically, Nabeel had made statements over Twitter directed at the Prime Minister of Bahrain, stating that he should resign and that his welcome in a village in Bahrain had been due to people receiving State subsidies. The Government imprisoned him in part due to these statements, which it stated were “publicly vilifying Al-Muharraq citizens and questioning their patriotism with disgraceful expressions posted via social networking sites.” The government convicted him on these charges, among others, and sentenced him to a prison sentence. The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention specifically found Nabeel’s detention on these grounds to be arbitrary in character, stating that it fell under Category II concerning

Nabeel’s current case is functionally analogous to his previous instance. In this case, as in the last one, Nabeel posted statements to Twitter that the government believed to be of a false character. In this case, as in the last, the statements that Nabeel made were of a political character protected through the right to free expression guaranteed by the ICCPR. As a result, in this case, as in the last, Nabeel’s detention is arbitrary in nature and illegal under international law.

Application

Accordingly, because Articles 133, 134, and 216 are illegal under international law, because the reputation and national security exceptions do not apply to cases of speech advocacy for human rights, and because Nabeel has previously been determined to be arbitrarily detained in a fundamentally analogous situation, Nabeel’s present detention is illegal under international law. Nabeel’s actions constitute human rights-related speech protected under Article 19(b). He criticized the government for allegedly practicing torture and abuse in Jau Prison. He additionally criticized the government for joining the Saudi-led coalition in the war on Yemen. These actions constitute human rights advocacy actions within the meaning of General Comment No. 34, which states that acts of free expression in support of democracy and human rights are always protected by the ICCPR.

In charging Nabeel in relation to his acts of political speech made over Twitter, the Government of Bahrain has abridged upon his ICCPR Article 19(b) right to impart information regardless of frontier. Any charges, detentions, convictions, or sentences, or any other form or governmental persecution, in relation to these acts, constitute violations of Bahrain’s state obligations to the international community and personal obligations to its resident Nabeel under the ICCPR.

Conclusion and Remedy

In examining both the law as provided by the ICCPR as accepted by the Government of Bahrain, as well as in examining previous cases that were functionally similar to the present case, it is clear that Nabeel’s present detention is illegal under international human rights law. In its decision regarding his previous incarceration, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention decided that the government should immediately release Nabeel and provide him with an enforceable right to due compensation in accordance with Article 9, Paragraph 5 of the ICCPR.[10] As this case is functionally identical to the previous case, the government should undertake similar remedy in the present instance. It must release Nabeel immediately and provide him with compensation commensurate with the duration of his illegal imprisonment.

- Abuse and Ill Treatment

Facts

Shortly after arresting Nabeel on 13 June 2016, the Government of Bahrain placed him in solitary confinement in East Riffa Police Station. Nabeel reported that the cell in which the government detained him was filthy and full of insects. In particular, the toilet in the cell was dirty and smelled of refuse. Nabeel asked the police station to clean the cell, but they refused. His family attempted to bring him cleaning agents so that he might clean the cell himself, but the government interdicted the cleaning agents and refused to provide them to Nabeel. Nabeel reported that the conditions of his cell kept him from using the toilet, sleeping properly, and bathing adequately.

On 21 June, Nabeel informed the public prosecutor that he suffers from chronic gallstones and skin conditions. The prosecutor referred him to the Bahrain Defense Force hospital, where a government doctor confirmed that Nabeel suffers from these conditions. The doctor stated that Nabeel requires surgery in order to remove the gallstones. Nabeel also complained that the unsanitary conditions of his cell had exasperated his skin condition. To date, the government had refused to provide treatment for the gallstones.

On 26 June, Bahraini authorities transported Nabeel to West Riffa Police Station. They have continued to confine him in isolation, and he has now been held in solitary confinement for over one month. The confinement is briefly interrupted by visits with his family. Nabeel states that confinement can also occasionally be interrupted by the government placing another prisoner in his cell, but that this prisoner is never able to speak languages in which Nabeel can communicate and often appears to be a drug addict and unable to communicate. Solitary confinement is otherwise continuous. Nabeel has not been allowed to exercise outside or fraternize with other prisoners. Nabeel, his attorney, and his family have all stated that the nature of his confinement has caused him significant mental anguish.

On 28 June, Nabeel again visited the Bahrain Defense Force hospital, where a doctor diagnosed him with an irregular heartbeat. Nabeel’s family states that this is a new condition from which he has not previously suffered, and believes that his incarceration has caused his illness.

Pertinent International Law

The ICCPR and provides international law on the conditions of detention. Article 7 of the ICCPR states in pertinent part,

“No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”[11]

Bahrain acceded to the ICCPR on 20 September 2006 with three reservations, none of which mention or affect the right to be free of abuse.[12] As such, the ICCPR fully controls upon the Government of Bahrain.

Further, the Convention against Torture (CAT) also provides international law on the subject of the treatment of detainees. Article 1 of the CAT states the minimum acceptable standard for a definition of torture:

“For the purposes of this Convention, the term “torture” means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.”[13]

Article 4 of the CAT states that any act of torture must be regarded as a criminal offense.

- “Each State Party shall ensure that all acts of torture are offences under its criminal law. The same shall apply to an attempt to commit torture and to an act by any person which constitutes complicity or participation in torture.

- Each State Party shall make these offences punishable by appropriate penalties which take into account their grave nature.”[14]

Article 11 of the CAT requires that States guard against the use of torture in detention facilities.

“Each State Party shall keep under systematic review interrogation rules, instructions, methods and practices as well as arrangements for the custody and treatment of persons subjected to any form of arrest, detention or imprisonment in any territory under its jurisdiction, with a view to preventing any cases of torture.”[15]

Bahrain acceded to the CAT on 6 March 1998 with one reservation. The reservation pertains to dispute resolution between State Parties, and does not substantively effect Bahrain’s obligations regarding the prohibition against torture.[16] As such, the substantive provisions regarding the treatment of prisoners apply in full force upon the Government of Bahrain.

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, otherwise known as the Mandela Rules, provide guidance on when a State violates a prisoner’s right to be free from abuse. Although not binding, States have, at a minimum, a duty to protect against abuse of prisoners, and the Mandela Rules may guide the determination of when that duty has been violated. The Mandela Rules state in pertinent part in Article 10:

- All accommodation provided for the use of prisoners and in particular all sleeping accommodation shall meet all requirements of health, due regard being paid to climatic conditions and particularly to cubic content of air, minimum floor space, lighting, heating and ventilation.[17]

And further in Articles 12-14:

- The sanitary installations shall be adequate to enable every prisoner to comply with the needs of nature when necessary and in a clean and decent manner.

- Adequate bathing and shower installations shall be provided so that every prisoner may be enabled and required to have a bath or shower, at a temperature suitable to the climate, as frequently as necessary for general hygiene according to season and geographical region, but at least once a week in a temperate climate.

- All parts of an institution regularly used by prisoners shall be properly maintained and kept scrupulously clean at all times.[18]

Further, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) describes international law having a bearing upon the right to health. According to Article 12 of the Convention,

“1. The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

- The steps to be taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include those necessary for:

(a) The provision for the reduction of the stillbirth-rate and of infant mortality and for the healthy development of the child;

(b) The improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene;

(c) The prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases;

(d) The creation of conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness.”[19]

The Mandela Rules provide guidance on a prisoner’s right to health. Article 22(2) states:

(2) Sick prisoners who require specialist treatment shall be transferred to specialized institutions or to civil hospitals. Where hospital facilities are provided in an institution, their equipment, furnishings and pharmaceutical supplies shall be proper for the medical care and treatment of sick prisoners, and there shall be a staff of suitable trained officers.[20]

Discussion

Torture

The Bahraini government’s treatment of Nabeel Rajab constitutes torture within the meaning of the Convention against Torture and is therefore illegal under international law. Additional treatment constitutes cruel, unusual, or degrading punishment within the meaning of the CAT, and is also therefore illegal under international law.

Beginning on 13 June 2016, the Government of Bahrain began holding Nabeel in solitary confinement. This confinement has been interrupted by brief family and hospital visits and co-incarceration with non-communicative persons, as well as a change in incarceration location, but has been ongoing since the beginning of his incarceration. At time of writing, the government has held Nabeel in such solitary confinement for 45 days.

The Convention against Torture states that torture includes any act that induces severe mental suffering as punishment for an act the victim committed. In this case, the solitary confinement had caused Nabeel significant mental suffering, and has been performed as punishment in the form of incarceration. International studies performed by independent experts on the subject of torture have confirmed that solitary confinement can result in sufficient mental anguish as to trigger the definition under the Convention against Torture, and may cause psychotic disturbances included “anxiety, depression, anger, cognitive disturbances, perceptual distortions, paranoia and psychosis and self-harm.”[21] The Special Rapporteur on torture and other forms of cruel, unusual, and degrading treatment or punishment has stated that any solitary confinement lasting more than 15 days de facto constitutes an act of torture.[22] The government has subjected Nabeel to solitary confinement for 45 days. Because the government’s solitary confinement of Nabeel is an act that has inflicted severe mental suffering as punishment against a crime, and because it has lasted longer than the 15 day period stated by the Special Rapporteur to constitute de facto torture, it constitutes torture and is therefore illegal under international law.

The government would counter by stating that it interrupts Nabeel’s solitary confinement with periods in which it places another prisoner in his cell. This argument does not have merit; it is not the act of the solitary confinement that causes torture, but rather any act that causes extreme mental anguish to Nabeel. Put another way, the measurement must be the effect the actions have on the victim, in this case Nabeel. In this instance, the government appears to intentionally interrupt Nabeel’s solitary confinement by placing in his cell someone with whom he cannot communicate or with whom he cannot socially interact. As a result, the net effect upon Nabeel is the same: because he cannot communicate with the person or interact socially, he suffers from similar if not identical anguish than he would if he were confined solitarily. As a result, the brief interruptions have no effect on the legality of his treatment; because the actions are purposeful and cause him extreme mental stress and psychological effects, they constitute torture within the meaning of the CAT definition.

The government’s treatment of Nabeel also constitutes cruel, unusual, and degrading punishment. Both the ICCPR and the CAT require that the government provide Nabeel with a sanitary cell in which to serve his incarceration. The Mandela Rules state that, at a minimum, cells should allow for bathing, sleeping, and the use of a toilet. The Rules further provide that Nabeel’s cell should be kept “scrupulously clean.”

The conditions of Nabeel’s detention do not adhere to the Mandela Rules requiring cleanliness in an incarceration facility. According to Nabeel, his initial cell was “filthy” and filled with insects. Nabeel further stated that the toilet in the cell smelled of refuse. He contended that the conditions of his incarceration kept him from using the toilet, bathing, and sleeping. Shortly after his incarceration in these unhygienic conditions, Nabeel developed a serious medical condition in his irregular heartbeat. Nabeel had never experienced this medical condition before. Although Nabeel has since been moved to a different facility, he states that the conditions there are also unhygienic. Because the conditions in Nabeel’s cell are not scrupulously clean, because they have prevented him from bathing, sleeping, and use of the toilet, and because they appear to have caused him illness, they constitute cruel, unusual, and degrading treatment within the meaning of the CAT, and are also therefore illegal under international law.

Access to Medical Treatment

The Bahraini government’s withholding of medical treatment in relation to Nabeel Rajab’s diagnosed medical conditions violates the ICESCR, and is therefore illegal under international law. According to Nabeel, a government doctor has diagnosed him with gallstones, skin conditions, and an irregular heartbeat. The doctor told him that he requires surgery for his gallstones. He has received no treatment for these conditions. The ICESCR states that the Government of Bahrain must recognize and take steps to ensure Nabeel’s highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The Mandela Rules elaborate, stating that, because Nabeel has been told he requires specialist treatment, the government must provide him with such treatment. Because the government has failed to take such steps, and because the government has not provided him with specialist treatment necessary to ensure his health, the government’s actions have violated the ICESCR and are therefore illegal under international law.

Conclusion and Remedy

Because the government’s treatment of Nabeel Rajab constitutes torture and abuse, and because the government has withheld necessary medical treatment, the Government of Bahrain has violated both its State obligations to the international community as well as its personal obligations to Nabeel. The government must immediately halt Nabeel’s solitary confinement. In order to comply with standards regarding the fair treatment of prisoners, it must also either move him into a sanitary cell or ameliorate the unsanitary conditions in his current cell. Further, the government must provide Nabeel with treatment for his gallstones, skin conditions, and irregular heartbeat. Finally, the government must provide Nabeel with an enforceable right to compensation regarding his mistreatment and abuse.

- Conclusion

Both the incarceration and treatment of Nabeel Rajab are illegal under international law. By incarcerating him on the basis of his acts of free expression in advocacy of human rights, the Government of Bahrain violated its commitments under Article 19(2) of the ICCPR. By torturing Nabeel, the Government of Bahrain violated its commitments under Article 7 of the ICCPR and generally under the CAT. By failing to provide Nabeel with medical treatment, the Government of Bahrain violated its commitments under Article 12 of the ICESCR. In order to comply with its commitments under international law, the Government of Bahrain must immediately release Nabeel and provide him with an enforceable right to compensation for his imprisonment and abuse.

James Suzano, Esq., is the Director of Legal Affairs at Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain. He is a member in good standing of the New York State Bar, and received his J.D. from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) School of Law.

[1] Government of Bahrain, “Bahraini Penal Code, 1976,” 1976, available at https://www.unodc.org/res/cld/document/bhr/1976/bahrain_penal_code_html/Bahrain_Penal_Code_1976.pdf.

[2] United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171 and vol. 1057, p. 407 (procès-verbal of rectification of the authentic Spanish text); depositary notification C.N.782.2001.TREATIES-6 of 5 October 2001 [Proposal of correction to the original of the Covenant] and C.N.8.2002.TREATIES-1 of 3 January 2002 [Rectification of the original of the Covenant].

[3] UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3aa0.html [accessed 27 July 2016].

[4] United Nations Human Rights Committee, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights General Comment No. 34, 12 September 2011, CCPR/G/GC/34, available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/docs/gc34.pdf.

[5] Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, Decision No. 12.2013, available at https://www.fidh.org/en/region/north-africa-middle-east/bahrain/14301-the-un-finds-the-detention-of-nabeel-rajab-arbitrary-it-is-urgent-to

[6] See generally, Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, “Documents.” http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?m=117

[7] Bahraini Penal Code, Ibid. note 1.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, Ibid. note 5.

[11] ICCPR, Ibid. note 3.

[12] UN General Assembly, Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 10 December 1984, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1465, p. 85, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3a94.html [accessed 27 July 2016].

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 1465, p. 85, available at https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-9&chapter=4&clang=_en.

[17] United Nations, Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, 30 August 1955, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36e8.html [accessed 27 July 2016]

[18] Ibid.

[19] UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 16 December 1966, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 993, p. 3, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36c0.html [accessed 27 July 2016].

[20] Ibid. note 17.

[21] U.N. General Assembly, “Torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment: A note from the Secretary-General,” 5 August 2011, UN Doc A/66/268, available at http://solitaryconfinement.org/uploads/SpecRapTortureAug2011.pdf.

[22] Ibid.