This is the first installment in ADHRB’s series assessing Bahrain’s National Report on its Universal Periodic Review implementation status. For the second installment, click here, and for the third installment, click here.

In advance of Bahrain’s third four-year cycle of the Universal Periodic Review of Human Rights (UPR), the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has published the Bahraini governments’ National Report to the UPR Working Group in all five UN languages. Much like the government’s 2014 UPR midterm report, however, the information contained in the National Report is purposefully misleading, vague, and incomplete. In fact, rather than expand on the midterm report, the full National Report largely repeats the same illusory claims to progress made up until 2014, all the while omitting the dramatic escalation in human rights violations – and the reciprocal regression on key UPR recommendations – that has occurred since late Spring 2016.

Despite an official submission date of 13 February 2017, the government’s National Report entirely neglects to address several enormous steps away from the reform program set by both the UPR and the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI): 1) the restoration of domestic law enforcement authority for the National Security Agency (NSA); 2) the advancement of a since-confirmed constitutional amendment to allow military courts to try civilians; 3) the execution of three torture victims, ending a de facto moratorium on capital punishment; and 4) the use of live ammunition against peaceful demonstrators, leading to the death of 18-year-old who was shot in the back of the head.

Bahrain’s National Report presents an accurate picture of neither the government’s adherence to its UPR commitments nor the country’s true human rights situation. Rather, from the outset of the report, the Bahraini government indicates that its efforts to contain “unlawful practices, acts of violence and terrorist threats” take precedence over human rights, and that these forces – rather than state negligence or repression – are ultimately responsible for “undermin[ing] the reform process.” Not only does it fail to address the authorities’ systematic exploitation of Bahrain’s broad anti-terror legislation to violate rights to free expression, privacy and due process, the National Report actually lists such legislation as a key component in the “Normative and structural framework for the promotion of respect for and protection of human rights” – a lengthy subsection that accounts for roughly 23% of the document and explicitly lacks any connection to specific UPR recommendations.

The government also fails to give an accurate account of the report’s methodology, which itself belies the veracity – and even intention – of the report. According to Section II.A, the Foreign Ministry – which chairs Bahrain’s High Coordinating Committee for Human Rights and is responsible for preparing the UPR National Report – consulted with “relevant official bodies” and “13 [civil society] associations concerned with human rights.” However, independent Bahraini or Bahraini diaspora human rights organizations did not receive such notice of consultation, including Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB), the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR), and the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD). More still, the government failed to note that the authorities have specifically prevented members of these groups and other human rights defenders or political activists from traveling to and engaging with international human rights mechanisms such as the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) and the UPR. ADHRB directly contacted the Government of Bahrain requesting to participate in the national consultation process, and was rejected; an ADHRB officer even submitted a 12-page visa application and formal request to travel to Bahrain to take part in the consultation, including a full itinerary, and never received a response.

Instead of engagement and consultation with independent civil society, the Bahraini government has actively sought to restrict and – in many cases – eliminate it. Though the National Report claims that “four new rights associations have been established, in addition to the nine already in existence” over the last three years, it is unclear what these organizations are and who make up their membership. These figures are likely skewed, however, by government-organized NGOs (GONGOs) that are funded and/or sponsored by the authorities and that do not face the same restrictions as independent groups. The government typically does not apply certain aspects of the law to GONGOs, and many contain government officials. In contrast, BCHR, the Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights, the Bahrain Human Rights Observatory, the Bahrain Nursing Society, the Bahrain Human Rights Society, the Bahrain Teacher’s Union, the Bahrain Medical Society, the Bahrain Lawyer’s Society, the Authors and Writers Family Society, and even the Bahrain Photographic Society, among others, have all been subjected to arbitrary forced dissolution or some form of judicial harassment, including the imprisonment of members. The government has similarly dissolved or launched dissolution proceedings against most major opposition political societies, including Amal, Al-Wefaq, and Wa’ad. As recently as 4 April 2017, Bahraini authorities prevented Sayed Hadi al-Mousawi, a former member of Al-Wefaq, from traveling to Geneva to take part in a pre-session event for Bahrain’s upcoming UPR.

Finally, the government’s National Report simply declines to provide a full recommendation-by-recommendation self-assessment of implementation status, choosing instead to disclose partial lists of government action relevant to a particular thematic set of recommendations (e.g. “Nationality”). Section II.B indicates that Annex I – which has yet to be published by OHCHR – contains a “summary table of recommendations,” but this ostensibly comprises information already “indicated in the body of the report” and likely does not provide concrete assessments of implementation status. This flawed reporting procedure prevents civil society groups and other stakeholders from compiling statistics and comparing implementation assessments.

Ultimately, the National Report offers no new evidence or information that would compel ADHRB to alter the assessment made in our shadow report, Bahrain’s Third Cycle UPR: A Record of Repression, released in conjunction with BCHR and BIRD earlier this year. To the contrary – it largely confirms our conclusion that the government has so far refused to take the UPR’s reform program seriously. As at times conceded in the National Report itself, we find that the Government of Bahrain has entirely failed to implement 133 of its 176 recommendations, made technical progress toward 23, and partially implemented just two. No one recommendation saw full implementation during the period under review, and the remaining 18 were rejected by the government. The National Report serves only as a further example of the Bahraini government’s attempts at obfuscation and self-aggrandizement on the international stage – efforts it invests more resources in than both substantive engagement with international human rights mechanisms and tangible domestic reform.

Selected Assessments of Bahrain’s National Report: Introduction and Part I

ADHRB, BCHR, and BIRD’s full UPR assessment can be found here, but we will also be presenting selected assessments of the National Report’s specific claims in advance of Bahrain’s review in May 2017. Assessments contain excerpted information from our full UPR report – which itself contains more than 8.5 times the amount of material submitted in government’s National Report – as well as additional or new information, where relevant. Below you will find the first installment of these selected assessments.

National Report: Section III.A, Para. 15 – “The application of constitutional…guarantees to ensure respect for the human rights of citizens and residents of has been reaffirmed.”

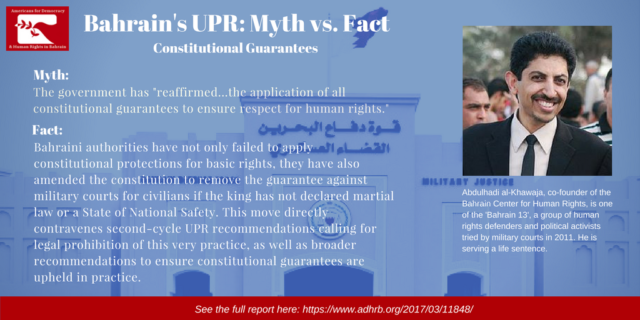

Brief Assessment: The government has entirely failed to practically apply a range of constitutional guarantees, from protections for free expression to prohibitions on torture and discrimination. Moreover, the government has actually removed constitutional guarantees that partially protected due process rights and expanded the role of military courts – a move that explicitly violates accepted UPR recommendations like 115.119, which calls for a formal proscription on “civilians being tried in military courts in the future.” Over the first several months of 2017, both houses of Bahrain’s National Assembly approved an amendment to Article 105(b) of the 2002 constitution, which prohibited the use of military courts to try civilians unless the king had declared a state of safety or martial law. On 3 April, the king confirmed the amendment and it became law. Now, the constitution permits military courts to try civilians accused of threatening national security or for terror offenses, the definition of which includes criticism of government institutions and other forms of basic dissent and expression.

King Hamad previously granted military courts wide powers to try civilians when he declared a State of National Safety in March 2011, facilitating the suppression of pro-democracy protesters. The National Safety Courts (NSC) prosecuted at least 300 protesters according to the BICI. Among those tried in the NSC were doctors, nurses, and the Bahrain 13, a group of political leaders and human rights defenders sentenced to between five years and life imprisonment. The BICI found that “fundamental principles of a fair trial, including prompt and full access to legal counsel and inadmissibility of coerced testimony, were not respected” in these courts.

National Report: Section III.A, Para. 21 – “All the judgments handed down by the National Safety Courts have been reviewed…the prosecution has dropped all charges that interfere with the right to and exercise of freedom of expression, namely, charges of inciting hatred against the ruling regime and broadcasting false news or rumours that could undermine security and public order.”

Brief Assessment: In the aftermath of the 2011 unrest, the government did not guarantee new trials for all civilians convicted by the NSC as recommended by both the BICI and the second UPR cycle – contrasting with mere “reviews,” as implied by the National Report. Instead, in many cases, the standard courts continued the work of the NSC and declined to throw out evidence obtained through torture or under duress. In 2013, the US Department of State found that although the “authorities transferred a majority of high-profile cases from the NSC to the civilian courts, the transfers generally do not result in new trials…[and] judges continue to permit trial records and evidence used in the NSC to be used in the civilian courts.” The State Department was here referring to the Bahrain 13, all but two of which remain in prison on charges stemming from free expression, assembly, and association – despite the National Report’s claim that charges related to free expression were dropped. Another 19 verdicts issued by the NSC in 2011 only faced review by a government panel and were not transferred to standard courts for reconsideration. Though some NSC cases did ultimately receive retrials in civilian courts per Royal Decree No. 62/2011, these retrials have also failed to meet international standards of due process and transparency as a result of serious flaws within the standard judiciary.

Moreover, while the Bahraini government acknowledges here that charges like “inciting hatred against the ruling regime” and “broadcasting false news or rumors that could undermine security and public order” violate free expression, it has continued to issue these charges against human rights defenders and political activists. In March 2017, for example, the government charged Ebrahim Sharif, a leader of the secular, leftist Wa’ad political society, with “inciting hatred against the regime” and against “factions of society” under articles 165 and 172 of Penal Code for tweets he had posted. Sharif was previously imprisoned from 2011 to 2015 for his involvement in the 2011 protest movement, and again from 2015 to 2016 for a political speech he gave. His political society, Wa’ad, is currently in the process of being dissolved by the Ministry of Justice for allegedly inciting hatred.

Similarly, in June 2016, the authorities the rearrested Nabeel Rajab, one of the country’s most prominent human rights defenders and the president of BCHR, on charges of “spreading rumors and false information” in relation to tweets, interviews, and editorials. He could face more than 16 years in prison if convicted. Rajab remains detained.