On Monday, 13 June 2016, Bahraini authorities arrested prominent human rights defender and president of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR), Nabeel Rajab. This recent arrest came on the first day of the 32nd session of the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) in Geneva, Switzerland. Bahraini authorities gave no reason for the arrest at the time, but later charged Mr. Rajab with “spreading false news and rumors about the internal situation in a bid to discredit Bahrain.”

At a US State Department briefing on Tuesday, 15 June 2016, Spokesperson John Kirby stated that the US has expressed its concerns with the Bahraini government in response to Rajab’s arrest and several other cases. Towards the end of the briefing, Kirby noted that Bahrain has been  a strong and important security ally to the US in the Middle East. He said that Bahrain and the US have “a strong bilateral relationship, and we greatly appreciate the assistance of Bahrain and the fact that they host our Fifth Fleet there and their contributions in the region to larger security and counterterrorism efforts.”

a strong and important security ally to the US in the Middle East. He said that Bahrain and the US have “a strong bilateral relationship, and we greatly appreciate the assistance of Bahrain and the fact that they host our Fifth Fleet there and their contributions in the region to larger security and counterterrorism efforts.”

While not an explicit justification for the State Department’s reluctance to take a stronger position on human rights issues in Bahrain, Kirby’s statement reflects a wider trend in the US foreign policy establishment to create a false divide between ‘security’ and ‘human rights.’

In April 2016, Secretary of State John Kerry traveled to Bahrain to meet with the country’s Foreign Minister, Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa, to discuss the conflicts in Syria and Yemen. There, Kerry described Bahrain as a “critical security partner,” and praised the king and foreign minister for the “seriousness” with which they have taken human rights. When specifically asked during a press briefing whether Bahrain has made sufficient progress on human rights, Kerry was largely silent. Instead, Kerry voiced criticism of Bahrain’s opposition for boycotting the last election, an action which he said “polarizes things instead of helping.” Several months after Kerry made these comments, the government closed the main opposition party, Al-Wefaq. And last week, the State Department released a report on the implementation of the BICI recommendations, which accepted much of the Bahraini government’s obfuscation as actual progress – despite persistent human rights violations.

To uncritically emphasize Bahrain’s role in the US’ regional security strategy over human rights concerns, however, is to ignore the heightened risk of instability driven by Bahraini authorities at home. The Government of Bahrain, which operates as a de facto absolute monarchy, has recently intensified its suppression of peaceful assembly and free speech. Rather than expand the space for dialogue or the expression of grievances, the government has disbanded civil society organizations, imprisoned human rights defenders, and expelled dissenting religious leaders – all in just over a week. The authorities have made it clear that there are no safe outlets for peaceful criticism, exacerbating the ever-present risk of mass unrest.

Beyond punishing non-violent dissent, the Bahraini government has marginalized its majority Shia population and instigated sectarian divisions within the country. The government has destroyed numerous mosques with historical, cultural, and religious importance to its majority Shia population. In 2011, for example, the authorities demolished the Al Barbaghi mosque, which is considered to be one of the most important mosques to Bahraini Shia and was built in 1549.

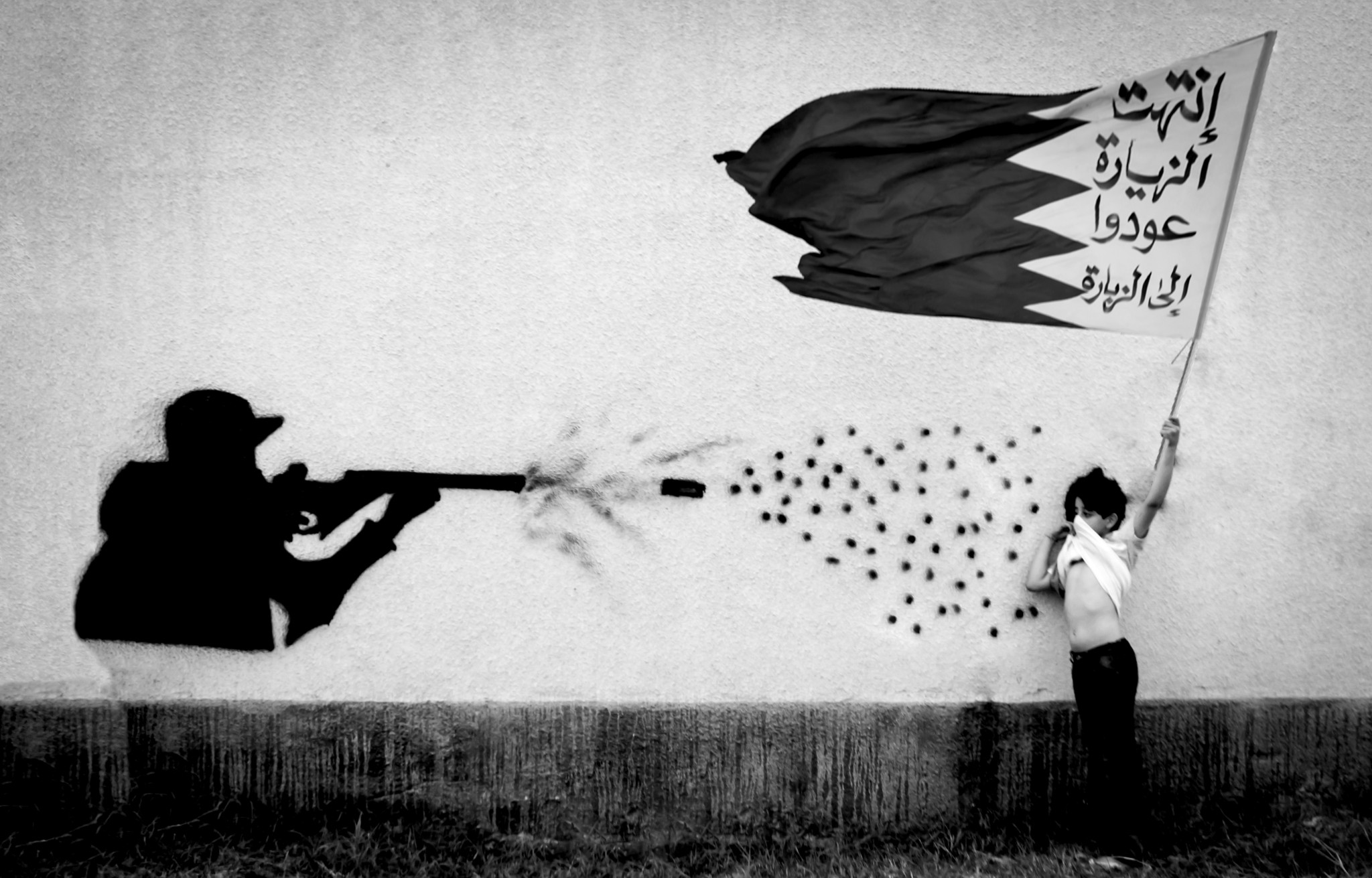

Furthermore, Bahraini security forces consistently use excessive force when dealing with the predominantly Shia opposition. In November 2014, a video surfaced of Bahraini security forces launching tear gas canisters into a Shia mosque. In the video, women are seen coughing and gasping for air as men outside break windows to try and rescue them. This occurred during Muharram, the most sacred month in the Shia calendar. ADHRB’s documentation indicates that authorities have regularly used dangerous amounts of tear gas in Shia communities, disproportionately injuring and killing Shia citizens.

Additionally, the Bahraini government has used or endorsed hate speech to provoke sectarianism and division. Mohammed Khalid, an ex-member of the Bahraini parliament known as @boammar on Twitter, has openly used the derogatory terms ‘Majoos’ (Magi) and ‘Rafadhi’ (rejectionist) to attack Shia on social media. He has called for direct violence against the Shia community, demanding that ‘Safawi’ (Arabic for Safavid) ‘terrorists’ be punished with amputation. One of his tweets read: “teargas will not help with the terrorist Iran slaves who want to kill security men. Shotgun, live bullets, and deportation is the medicine they deserve.”

Such vitriolic sectarian discourse has contributed to violence in a number of states across the Middle East and North Africa, most notably in Iraq and Syria. From January 2013 to January 2016, Mercy Corps conducted public polling across Iraq asking citizens their opinions of violent extremism. What they found was a link between perceptions of injustice and support for violent extremism. Furthermore, most Iraqis who were polled felt that they had been discriminated against based on their ethnicity or sectarian group. According to Hassan Hassan, coauthor of ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror, the government’s marginalization of Sunni Iraqis was a contributing factor to the rise of ISIS.

While Bahrain has not broken into armed conflict as in like Syria and Iraq, the government has created a violent cycle of unrest and repression that has intensified dangerous sectarian divisions. The US must reframe its ‘critical security relationship’ with the Bahraini government to account for its systematic human rights violations – ones that, unchecked, may ultimately destabilize the country and the Gulf region. As recently noted by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid bin Ra’ad al-Hussein, “Repression will not eliminate people’s grievances; it will increase them.” The US must recognize that this sort of ‘security’ is unsustainable.