Below you will find the third installment of Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)’s assessments of claims made in the Bahraini government’s National Report to the United Nations (UN) Universal Periodic Review (UPR) Working Group. Assessments contain excerpted information from the full UPR assessment issued by ADHRB, the Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR), and the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), as well as additional or new information, where relevant.

The full UPR assessment can be found here, ADHRB’s overall response to the government’s National Report and Part I of the assessments can be found here; and Part II of the National Report assessments can be found here.

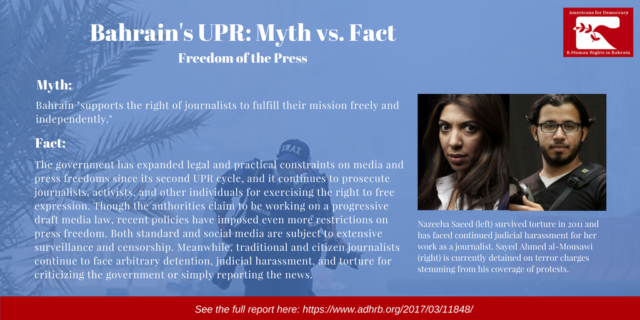

National Report: Section III.A Paras. 65, 69 – “The Kingdom of Bahrain supports the right of journalists to fulfill their mission freely and independently and…guarantees that no journalist may be arrested, imprisoned, intimidated, oppressed or humiliated for exercising the legal and constitutional right to freedom of expression….Bahrain welcomes the entry of journalists and foreign media in accordance with international standards.”

Brief Assessment: The Government of Bahrain has made almost no effort to implement greater protections for media and press freedoms since its second UPR cycle, and it continues to prosecute journalists, activists, and other individuals for exercising the right to free expression. Though the government claimed in 2012 that a new draft media law “designed to ensure freedom of expression and reduce restrictions on the media” was “in its final stages of debate,” it has yet to implement any such law. More still, recent government draft resolutions on the media suggest that the law will likely provide wider grounds for the criminalization of free expression and specifically political commentary, such as by requiring journalists to “respect the kingdom’s sovereignty, system of governance, icons, institutions and statutory bodies.” Both standard and social media remain subject to extensive surveillance and censorship. Meanwhile, traditional and citizen journalists continue to face arbitrary detention, judicial harassment, and torture for criticizing the government or simply reporting the news.

Just this year, the government temporarily suspended Al-Wasat, the country’s only independent newspaper, in the wake of a state execution of three torture victims accused of terror crimes, including a young blogger. The authorities have repeatedly targeted Al-Wasat for censorship and other forms of judicial harassment, such as in 2011, when the newspaper’s cofounder, Abdul-Karim Fakhrawi, was tortured to death in the custody of the National Security Agency (NSA), the country’s recently re-empowered intelligence body.

During the period under review, the government arrested or otherwise harassed dozens of journalists, including Ahmed Fardan, Hussain Hubail, Mahmood al-Jazeeri, Ahmed Humaidan, Jaffar Marhoon, Qasim Zainal Deen, Faisal Hayyat, Nazeeha Saeed, and Sayed Ahmed al-Mousawi. Al-Mousawi, an award-winning photojournalist, was arrested, tortured, stripped of his Bahraini citizenship, and sentenced to 10 years in prison on accusations of providing SIM cards to alleged “terrorists.” He is currently appealing his sentence. One journalist, Ahmed Ismail Hassan, was shot and killed during the period under review.

Additionally, despite the National Report’s explicit assertion that Bahrain “welcomes the entry of journalists and foreign media,” authorities routinely impede the work of foreign press. Between February 2011 and February 2015, the government restricted the travel of at least 51 journalists from various international media organizations. In February 2016, security forces arrested and expelled American journalist Anna Day and three cameramen for covering the anniversary of the Arab Spring protests. Authorities previously arrested BBC and ITN British TV teams on similar grounds. Bahraini citizens who speak with foreign media are also at risk of reprisal, such as Ebrahim Sharif, the formerly imprisoned leader of the Wa’ad opposition society, who was charged with “inciting hatred against the regime” after he gave an interview to the Associated Press (AP) in November 2016. Although this specific case was dropped amid international outcry, Sharif was again charged with “inciting hatred” for social media posts in March 2017.

Bahrain remains among the lowest-ranked countries in the world in indices on press freedom. Reporters sans Frontières (RSF) ranked Bahrain 162 of 180 countries in its 2016 World Press Freedom Index and lowered it to 164 in its 2017 index, reflecting a steady deterioration in protections for press freedom. RSF described the kingdom as “notorious for jailing large numbers of journalists, especially photographers and cameramen.” In 2016, Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net report assigned Bahrain a score of 71/100 (where 100 represents complete restriction on online free expression and free press) and ranked it the 56th worst country for internet freedom out of the 65 countries it evaluated.

National Report: Section III.A Para. 85 – “The political aspect of the National Dialogue…ended in agreement upon a set of basic principles.”

Brief Assessment: The National Dialogue process, originally initiated to achieve a peaceful political resolution between the government and Bahrain’s main opposition societies, failed to achieve any substantive reform. Since 2011, the process has repeatedly started, stalled, and ultimately halted. Following the imposition of further restrictions on freedom of assembly and expression in 2013 – as well as the arrest and judicial harassment of opposition leadership – the opposition bloc withdrew from the most recent process and it collapsed in early 2014.The government has not restarted the process.

Though the authorities intermittently engaged the opposition in informal dialogue after the end of the official process, they dramatically intensified their suppression of these societies following the November 2014 parliamentary election. In December 2014, the government arrested and later imprisoned Sheikh Ali Salman, the leader of the largest opposition society Al-Wefaq, and in July 2016 they dissolved Al-Wefaq altogether. Similarly, the government sentenced Ebrahim Sharif, leader of the secular Wa’ad opposition society, to another year in prison in 2015 on charges related to the contents of a political speech he delivered. Though he completed the term last year, authorities have continued to judicially harass him and other members of Wa’ad on accusations related to free expression. In March 2017, the Ministry of Justice and Islamic Affairs launched legal proceedings to dissolve the society, which remain ongoing. Fadhel Abbas, leader of the leftist Al-Wahdawi society, was arrested for tweets criticizing the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen in March 2015, and a court later sentenced him to three years in prison on appeal.

In sum, the authorities have not only failed to take substantive measures to resume the national dialogue, they have actually taken steps to eliminate the opposition altogether, effectively precluding the prospects for further talks without a major reversal in government policy.