The crackdown on online expression by the Saudi Arabian government has been reported extensively. In 2014, Human Rights Watch (HRW) denounced Saudi prosecutors and judges for using vague expressions of terrorism to try Saudi citizens for peaceful tweets and social media activities. The counter-terrorism legislation was criminalising activity harming the public order, religious values, and the sanctity of private life. In 2017, Saudi Arabia decided to amend the terms of this legislation by promulgating a new counter-terrorism law. However, the law currently remains taunted by extreme repression of freedom of expression and by a vague definition of terrorism, which was criticised in the latest cycle of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Saudi Arabia.

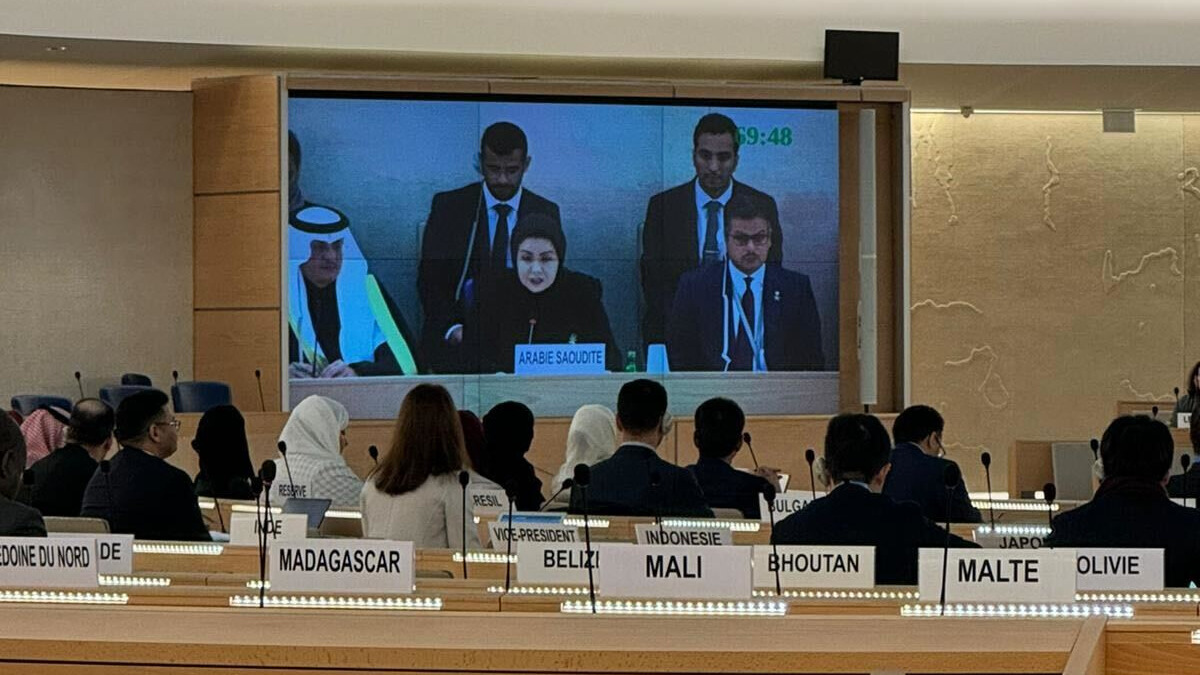

In particular, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, the United States, Canada and Switzerland have pointed out the flaws of counter-terrorism legislation in the 2024 UPR cycle. These countries requested Saudi Arabia more transparency in their definition of terrorism, in line with international human rights law standards. At the same time, these countries highlight the drawbacks of legislation that ideally grants safety to online platforms, which instead represses citizens’ freedom of expression. After the replacement of the 2014 counterterrorism law, the safety of the media has not improved. Rather, Saudi Arabia enhances fear among its citizens by putting them at risk of high fines or years in prison.

Freedom House, an agency classifying the freedom of the web, defines the internet platforms of Saudi Arabia as not free, lacking the possibility to access content and with various violations of users’ rights. In addition, internet users face extensive censorship and surveillance, with authorities systematically blocking websites or removing content. News from 2023 also informs that Saudi authorities manipulate online information to give a positive image of the government and its policies. Nonetheless, the most alarming concern with the ‘’misuse’’ of public platforms is the risk of being harassed or prosecuted. During 2023, there have been different cases of courts handing people to prison for their peaceful online expression or activism.

Repeatedly, ADHRB denounced the escalated widespread use of antiterrorism and cybercrime laws to target human activists. Sentences, fines and travel have characterised repression in the absence of minimum standards of fair trials. Amnesty International reports that at least 15 people have been sentenced to between ten and forty-five years for their peaceful online activities. Salma al-Shebab, PhD student at the University of Leeds, recently saw her sentence increased in appeal to 34 years by the Specialized Criminal Court (SCC). Her sentence was caused by her support on Twitter for a women’s rights activist.

Overall, the counter-terrorism laws (including cybercrime) are highly repressive and put at risk the civil liberties of Saudi citizens. Concerns arise about broad definitions of terrorism in the national legislation, specifically when terrorism might include ‘’disturbing public order’’ or ‘’exposing national unity to danger’’. Furthermore, the courts have been accused of being bodies that report directly to the king, failing to separate the distinction between judiciary and executive. ADHRB is highly concerned about anti-terrorism laws in light of the failing premises of Saudi Arabia to amend its rules. Controlling Twitter and other public platforms risks further jeopardising human rights status in the Kingdom. ADHRB recommends states use their diplomatic platforms to convince Saudi Arabia to amend its counter-terrorism laws. In addition, it urges international bodies to initiate investigative mechanisms for countries repressing freedom on social media platforms. Finally, it reiterates civil society organisations’ relevance in denouncing human rights abuses.